Making Good Group Decisions, Effectively

Good decision-making is good process, used intentionally. Key lessons and principles to apply in your practice.

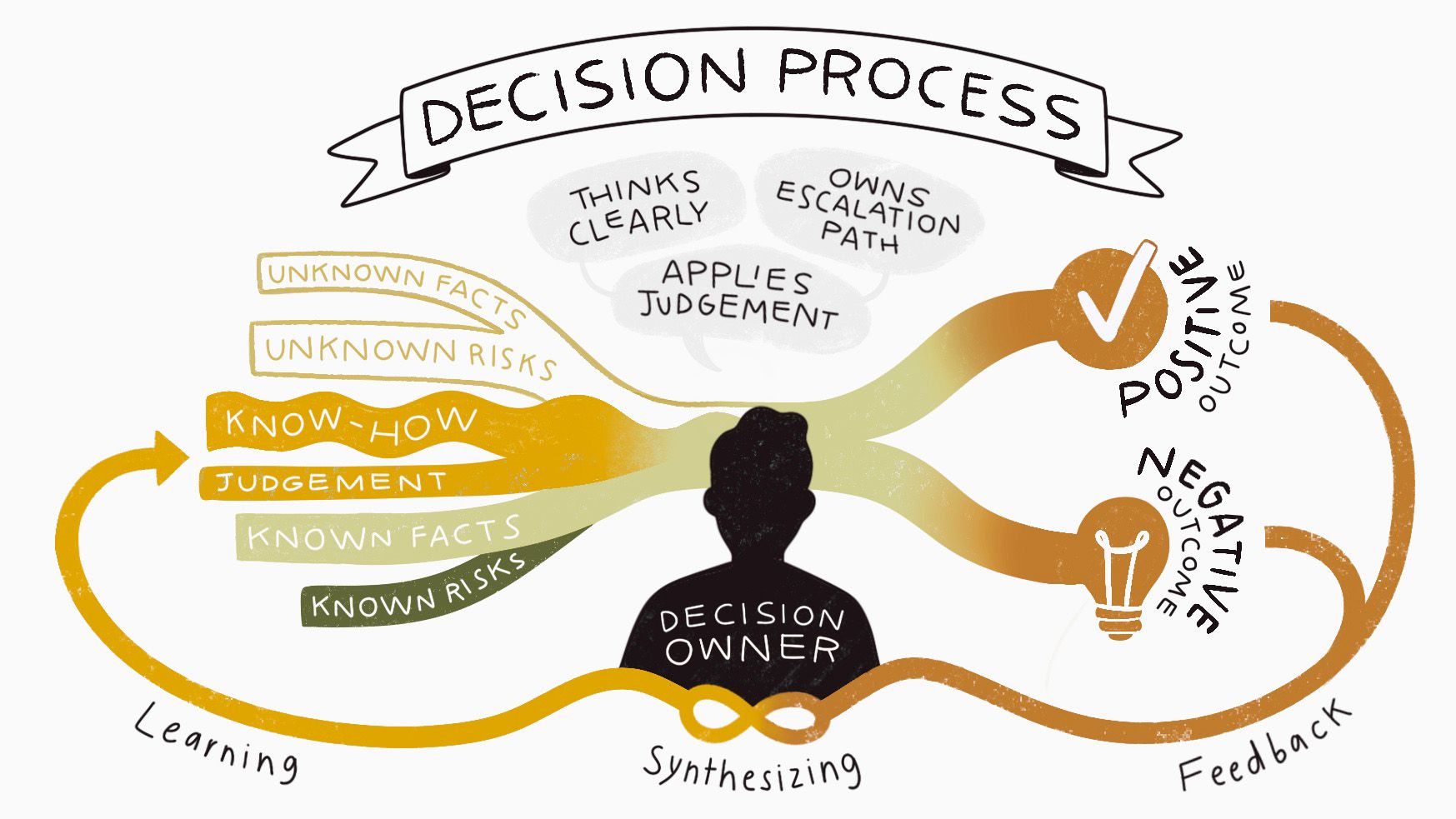

Good decisions may not always result in good outcomes

That does not mean it was a bad decision. All non-trivial decisions are made with imperfect information, and a good decision is the result of a good process that accurately captures our state of knowledge (known-knowns), acknowledges risks (known-unknowns), and builds buffers and remediations for the known- and unknown-unknowns.

A positive result does not automatically signal good decision-making. Good outcomes can come despite bad decision-making and execution and, sometimes, through sheer luck. A negative result is a discovery and an opportunity to learn and improve future decisions; a negative result is only a failure if we fail to learn from it or if the failure is that of execution due to a lack of commitment or follow-through on the decision.

Don't judge decisions by outcomes. Focus on the quality of the thinking and intentionality of the decision process and the rate of learning from the resulting outcomes.

Decisions should be made at the right level

To increase velocity and execution, we need to enable people who have the best access to relevant information to make decisions. Those in the trenches and closest to the problem are usually the best suited to make the decision or winnow down the decision space to a few options. Don't block on consensus, optimize for velocity and learning. If the tradeoffs impact other areas or teams or have long-term implications that the group needs input on, escalate up with context and clarity.

Meet if you're optimizing for speed, write first for quality

Good decisions require clear thinking. Clear thinking requires sitting with the problem to understand it deeply: what decision is actually being made, the tradeoffs, and its potential second and third-order impact. Synchronous decision-making optimizes for speed, which is guided by intuition, pattern matching, and mental heuristics. It seems effective because it feels efficient, but it does not yield the same results.

Consensus building undermines velocity and ability to execute

We must strive for shared understanding and honest discussion of risks and disagreements, but we're not seeking to de-risk every decision—that's impossible, and very few decisions are one-way doors. Document the disagreements, agree to disagree, commit and execute with conviction. If you learn new information, come back and make another decision with updated context and lessons learned.

Decisions need to have a clear decision process owner

There should be a single and well-known process owner responsible for guiding the process: formulating the problem and communicating the agenda, engaging necessary stakeholders, integrating inputs and feedback, openly weighing the different options, summarizing, and making the decision. Not everyone might be happy with the outcome because all complex decisions are about mediating tradeoffs, and that is precisely why we have decision process owners: they guide the process and exercise judgment and leadership to allow the group to proceed.

Escalate with and through the decision process owner

Disagreement is healthy, backchannels and festering uncertainty are not. If you disagree, engage the decision-maker first and let them know about your objections. Escalate up, together, if you're unable to resolve the concerns. If you don't escalate, execute the decision as if it was your own and never seek to undermine it by complaining or attempting to block it on the side.

Subscribe to Ilya Grigorik's essays

Receive latest updates in your email inbox